From the Introduction to The Other Side of the Painting by Wendy Rodrigue, published October 2013 by UL Press-

My mom, an artist, talked me into my first Art History class, a sweeping journey from cave paintings to the start of the Renaissance. Previously, I avoided it, thinking I preferred self-discovery through my mother’s books. Yet from day one, I sat lost in another time and world. I imagined the hand that held the brush, something I still do, even with George’s paintings, even after I watched him apply the paint.

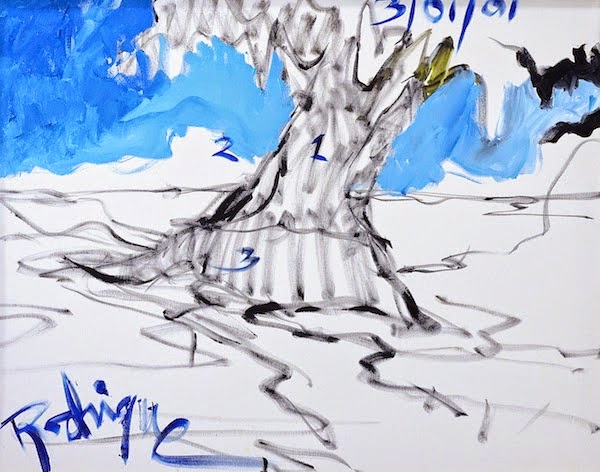

(pictured, George Rodrigue at his easel, Carmel, California 2013; click photo to enlarge-)

Somehow, imagining the artist puts me in that place, those circumstances, as close as I would ever come to inside his head. It’s been my obsession as long as I remember- to understand how others think and feel, why they do the things they do, and that somehow it’s all rooted in good. (…at which point George gives me the Hitler speech).

Simultaneous to early Art History, I took “Shakespeare’s Comedies and Histories,” also in the mid-1980s at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas, interweaving in my mind the stories, historical figures, language and art. In the library I discovered the media room where, in those pre-internet days, I watched the BBC Television Shakespeare, further enlivening not just history, but another’s spirit, whether Shakespeare’s, the character’s, or the actor’s, so that I might satisfy a small bit of my curiosity and learn who they are and how they tick.

(pictured, George Rodrigue at his easel, Lafayette, Louisiana, 1971; click photo to enlarge-)

Maybe it’s empathy, but I think it’s more. It’s an indefensible obsession, something that drives George crazy, as I chase down a rude waiter not to tell him off or kill him with kindness, the southern way, which was never my way, but rather to honestly find out if we’ve had a misunderstanding, if we offended him, or if a thoughtful word just might help a problem that has nothing to do with us at all. I lose sleep over these unsolved muddles, replaying conversations and missed opportunities in my mind.

And I believe that all of it makes me capable of better understanding the artist, any artist, so that even a concrete sandwich is someone’s personal expression. I may not relate to it or want it within my collection, but I respect it as coming from within someone else. (….again from George the Hitler speech, this time combined with the crappy art speech).

George shakes his head over my elation at the recent find of Richard III’s burial site and skeleton. I’ve watched the videos repeatedly of the dig and DNA discovery, imagining not that I’m the English King, but that I’m the archaeologist, enchanted by such a find. I imagine that the hand holding the tools is my hand, brushing away the dirt, carefully, revealing delicate finger bones, eye sockets and teeth.

Suddenly Art History, Shakespeare, History and Science coalesce into one magnificent, meaningful skeletal vignette. I run first to the internet and, dying of curiosity, to my mother’s books and my college books and to Shakespeare, blending it in my mind as it has in England on a university’s lab table.

I believe in integrating the arts into every aspect of education and as much as possible into daily life. This is why Louisiana A+ Schools (and similar programs in other states) is so exciting, along with a widespread move towards education awareness in museums. This is also why 100% of my proceeds from this book, as well as related lectures and exhibitions, benefit the programs of the George Rodrigue Foundation of the Arts, including art supplies for schools, college scholarships, and art camps.

I grew up in the artistic, near-theatrical bubble of Mignon, and today, more than twenty years since my last Art History class, I live in the environs of culturally rich New Orleans and naturally beautiful Carmel Valley, California. Every aspect of my daily life blends with the arts. My blog, Musings of an Artist’s Wife, allows me to observe and reminisce on paper, with posts lasting indefinitely, unlike a magazine that may end up in the trash or on the bottom of the bathroom pile.

My husband, George Rodrigue, is an artistic embodiment. For him, as he creates and makes decisions, the art always comes first. He refers to me often as an artist too. On school visits, however, you won’t find me painting with the kids. Instead I move through, admiring their work, envying a freedom of line unknown to me. I paint nothing. I draw nothing. Faced with a blank canvas, I feel only anxiety. Yet George wanted to subtitle this book, The Story of Two Artists, a title so uncomfortable that I barked my rejection without letting him explain.

More than "artist," the word "marketing" chills me, reducing my writing to a sales strategy. From the beginning, these Musings, whether in my blog, a magazine, or book, are based on one simple concept: sharing. Within my essays are my life’s interests. My hope is that what I find intriguing, most of which involves George Rodrigue, and all of which, thanks to the filter placed on me by my mother years ago, involves the arts, will inspire others, because, ultimately, the joy of my self-expression, whether through writing or public speaking, lies in that challenge.

Wendy

-learn more about The Other Side of the Paintinghere; order on-line at amazon or visit your favorite independent bookstore; order a special signed and numbered collector's edition at this link-

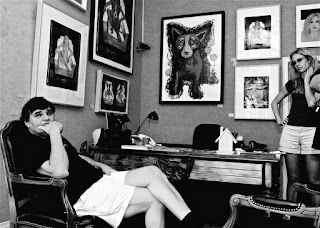

-pictured above, first book signing for The Other Side of the Painting, October 12, 2013, Carmel, CA; click photo to enlarge-

-first review, October 13, 2013, from the Lafayette Daily Advertiser, linked here-

-for more art and discussion, please join me on facebook-